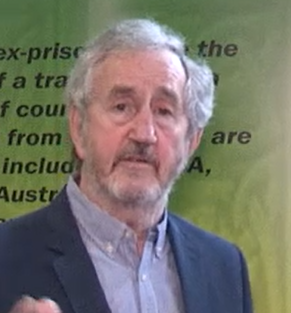

- I would like to share the background of the conflict in Ireland as I personally experienced it, and the path that led me to engage in non-violent forms of activism now.

People in the world tend to think that we Irish are -sort of- “British” because our country is situated very close to Britain. We have the same colour of skin, and mostly, we speak the same primary language, English.

Our perspective is different—we stress the importance of understanding the circumstances that led people to armed struggle. That understanding is crucial for grasping the historical depth of the 800-year conflict between the two countries.

Ireland was among the earliest territories to come under British rule, which, along with the introduction of the English language, brought about significant changes on the island in areas such as land ownership, religion, cultural practices, clothing, and daily life. As these changes took place over many centuries, many people may not be fully aware of the historical reasons behind the cultural similarities between the two countries today.

A lack of understanding about the historical context behind today’s situation is one reason why many people around the world may not fully grasp why Irish people took up arms to challenge English governance. The common narrative about those who physically opposed British rule often overlooks the historical background and focuses mainly on the idea that using armed struggle to claim national independence is wrong in today’s world, leading to labels such as “terrorist.”

From the perspective of people like myself, if colonisation was unfair many years ago, then some of its lasting impacts, which continue to affect people today, are also unfair. When political processes have not fully resolved these issues, it is understandable that people might explore different ways to seek justice. This helps to explain why many Irish people have been reluctant to accept the situation for an extended period.

India, a large former colony of Britain, gained its independence through peaceful means under the leadership of Gandhi. However, around the world, especially in Africa, former colonies of French, Italian, and Portuguese powers also achieved independence, often following armed struggles. South Africa is another notable example. People today forget that Nelson Mandela was arrested for being involved in an armed group that was considered illegal at the time.

Irish Republicans engaged in armed struggle from the late 1960s, but over time it became clear to us that political participation through elections could achieve similar goals. This political effort gained momentum with the election of Bobby Sands, an imprisoned IRA activist, in 1981. Since then, Sinn Féin has grown significantly and is now one of the leading political parties in Ireland.

For us Irish Republicans, the increasing support at the ballot box validated the actions taken by the broader independence movement. However, it also became apparent that the armed conflict with the British government was evolving into what seemed to be an internal conflict between different groups on the island, with the British acting more as neutral parties attempting to mediate this internal disagreement.

In response to concerns about one-sided portrayals in the media, many Republicans began engaging in dialogue with communities to reflect together on the path forward. In particular, they discussed whether it was appropriate to continue the armed struggle while also building momentum through political participation. Through these conversations held across the island, a clear message emerged. Ending the use of force could be a positive step and might help to strengthen broader support through the political process. Over time, this view proved to be accurate.

Simply put, resistance movements do not succeed through the efforts of those involved alone. They also depend on support from the communities around them and on shared reasons for that support. In the case of Ireland, the long period of conflict that lasted for more than twenty years was sustained both by the commitment of those directly involved and by the communities who stood with them.

In the same way, peace and an end to conflict cannot simply be declared from outside. For peace to take hold in a lasting way, there must be reasons that people understand and agree with. Those who had supported the struggle needed to know why a change in direction was being made and what that future might look like.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Sinn Féin gradually gained more support through elections across Ireland. This steady growth helped give many people the confidence that peaceful political efforts could replace armed struggle and become the main path forward.

In prison, I was one of those political prisoners who advocated trying a different route to achieve our goals. Many others were of the same mind, and we offered our views to our leadership outside of the prison.

In 1998, the Good Friday Agreement signalled a major shift in the political landscape in Ireland. Brokered by the United States government and agreed to by both British and Irish governments, the agreement signalled a clear route to lasting peace and structural political changes in Ireland. A major factor in the agreement was the promise of a referendum on the reunification of the island. Unfortunately, that has yet to be held.

Today, I am an advocate for the peace process, for dialogue and for building a much more democratic and fair society for all in a reunified Ireland.

Along with former British soldiers (our former enemy/opposition) who served in Ireland, we, former political prisoners, talk with university, community and school groups and explain our context for participation in the armed conflict. People all understand /'get it' once each narrative gives their context.

Today, I have come to believe that there is no need to fight for something that can be achieved through the electoral process.

The latter is the logic which I - and most of the people with whom I opposed British rule in Ireland- use today to explain the current political situation. I remain a political activist with Sinn Féin, and as long as I am able, I will continue my electoral activism to achieve my political goals. All wars/conflicts do have to end and allow dialogue to begin!! Having been through that process of various types of activism - armed and electoral- we gladly promote our story to anyone willing to listen. We have been invited to speak with many organisations in different parts of the world to explain our approaches to establishing and embedding the peace and building our platform for continuing our electoral progress.

Disclaimer: The views, information, or opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Global Taskforce for Youth Combatants and Accept International.